First let me get this off my chest. How can a respected newspaper allow this:

The Cassandras always proved wrong.

Cassandra's curse, lest we forget, was that although she was right, no-one would listen.

Cassandra's curse, lest we forget, was that although she was right, no-one would listen.

That feels a lot better. Onward.

The respected newspaper in question is the Wall Street Journal,1 in an article headlined New Limits to Growth Revive Malthusian Fears. It’s a long piece, which I won’t attempt to précis, but what is most interesting to me is that the prevailing view is that Malthus, unlike Cassandra, was wrong. That technological fixes can keep people, en masse, ahead of the resources we consume. The article goes well beyond that, ending with this salutary paragraph:

Indeed, the true lesson of Thomas Malthus, an English economist who died in 1834, isn’t that the world is doomed, but that preservation of human life requires analysis and then tough action. Given the history of England, with its plagues and famines, Malthus had good cause to wonder if society was “condemned to a perpetual oscillation between happiness and misery.” That he was able to analyze that “perpetual oscillation” set him and his time apart from England’s past. And that capacity to understand and respond meant that the world was less Malthusian thereafter.

I found the WSJ piece linked from a blog post at The Economist, which did its own bit of interpretation, about why the recent price rises seem to have taken everyone by surprise. Demographics, and the hitherto unequal distribution of demand seems to be the answer.

All of which triggered me to undefer a post I starred almost two weeks ago, an account at the Agricultural Law blog of the Ehrlich-Simon bet, 30 years on. I’ve been meaning to post about this since then, because I remember the original bet so clearly. I’ll let Andrew Torrance of AgLaw explain:

In 1980 three prominent Bay Area academics (Stanford's Paul Ehrlich and Berkeley's Johns Harte and Holdren) bet business economist Julian Simon that the real (inflation-adjusted) price of five commodity metals (that is, chromium, copper, tungsten, tin, and nickel) would rise by the year 1990. Far from being metal-heads, Simon and Ehrlich et al. chose these metals to stand in as representatives of other natural resources.

Over the decade of the bet the price of each metal did, in fact, decline in real terms. Simon, a libertarian and economic optimist, won the bet, receiving almost $600 from Ehrlich et al..

Torrance then goes on to ask the important question:

What if the bet had closed today rather than in 1990?

Inflation adjusted prices show that Ehrlich et al. would win on four of the five metals: copper, nickel, tin and tungsten. Simon wins chromium.

Economists, the whole world knows, are at best ambivalent on the long view. After all, was it not John Maynard Keynes who said, "Long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead."? And as a commenter to the Economist blog (adopting the cute pseudonym JKeynes, pointed out, “Anyone who believes that exponential economic growth can go on forever on a finite planet must either be a madman or an economist.” He was quoting Kenneth Boulding, another economist.2

Biologists understand the long view. And they understand something else about limits to growth. Bar a teeny bit of activity around hot vents in the stygian depths of the ocean, all life on Earth depends on the energy of the sun. In 1986 Ehrlich was one author of a wonderful paper entitled Human Appropriation of the Products of Photosynthesis. Take home message:

Nearly 40% of potential terrestrial net primary production is used directly, co-opted or foregone because of human activities.

Got that?

Humans then were “appropriating” nearly 40% of the sunshine being converted by plants on Earth into a usable form. Just what technological fixes are going to allow population to double and still leave enough of that net primary production for all the other living processes on which we depend?

I bang on about this paper and its conclusion at every opportunity, because I honestly don’t know why it isn’t widely known. It ought to have been some sort turning point, but it wasn’t.

Malthus, like all good Cassandras, like Ehrlich, was correct. Populations cannot simply keep growing geometrically. The question is, how long a long run are we prepared to consider? Like Keynes, should we stop worrying because we’ll be dead?

I don't think so.

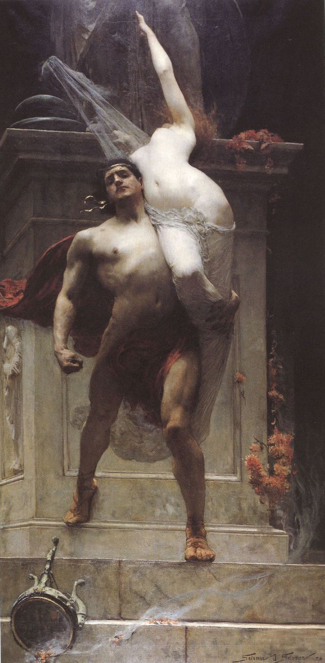

The picture? Ajax (the beast) and Cassandra, by John Joseph Solomon.

-

Yes, I know it's a Murdoch paper now, but self-respecting fish are still willing to be wrapped in it. ↩

-

2022-03-27: The comment is gone, but I know I saw it. ↩

Webmentions

Webmentions

Webmentions allow conversations across the web, based on a web standard. They are a powerful building block for the decentralized social web.

If you write something on your own site that links to this post, you can send me a Webmention by putting your post's URL in here:

Comments